Volume 19, Issue 37 (September 10, 2017)

“Lord, Open the King of England’s Eyes”

How the Bible Came to Us (10)

By Kyle Pope

Can you imagine a time when reading the Bible in your own language was a crime? What would it be like to live in a place where just to read God’s word you had to smuggle Bibles across the border like criminals do drugs or guns? The next time you open your Bible, stop and consider that when the Bible was first translated into English, that’s exactly how it was!

To set the stage, let’s travel back some 600 years. English sounded much different then. It had gradually developed out of the older language called Anglo-Saxon, spoken by tribes in the British Isles. According to the seventh century historian Bede, Christ was first preached in England in AD 156 (Ecclesiastical History 1.4), but Bibles of that time were in Latin. No complete translation of Scripture into Anglo-Saxon was ever made.

Any Scriptures the people had were only partial. In AD 735, Bede himself had translated the gospel of John into Anglo-Saxon, dictating the last verse shortly before his death (Letter from Cuthbert to Cuthwin). Unfortunately, no copies have survived. Alfred the Great (ca. 848-900), the king who defended England against Viking invasions, translated portions of Scripture and prefaced them onto his own laws. In his efforts to educate the people he may have translated some Scriptures from Latin to Anglo-Saxon (Aelfric, preface to Homilies), but if so none survived. The earliest surviving examples of Anglo-Saxon translations were in the form of glosses—word-for word translations written between the lines of Latin Bibles. These include two illuminated manuscripts of the Gospels from the tenth century (Lindisfarne Gospels, British Museum, Cotton MS Nero D.IV; Rushworth Gospels, Bodleian Library, MS Auctarium D. 2. 19) and a book of the Psalms from the time of Alfred (ca. 850) which is the oldest surviving translation of Scripture in Anglo-Saxon (Vespasian Psalter, British Museum, Cotton MS Vespasian A I).

The first stand-alone translation that seems to have gained some circulation was an edition of the gospels done around 990 in Wessex from a pre-Vulgate form of Latin. Seven manuscripts of the Wessex (or West Saxon) Gospels survive at Oxford, Cambridge, and the British Museum. Even these, however, were not complete translations of the Bible, and none of them were made from Greek or Hebrew (the original languages of Scripture).

A complete translation of the Bible into English would come in connection with the work of John Wycliffe—a professor at Oxford. After the development of Roman Catholicism, the Vatican exercised great control over the churches in England. Catholics taught that church leaders had received authority from God to direct the church in accordance with their will. Common people were not encouraged to read the Bible, but were required to follow the Catholic priests and bishops who answered to the pope in Rome. Wycliffe rejected this view and began teaching that the Bible was the source of all divine truth. He believed it should be read by all people to know God’s will. His opponents called his followers Lollards (a name meaning “mutterers”). Wycliffe died in 1384, but his work continued. In 1394, John Purvey, his friend and secretary, finished a complete translation of the entire Bible from the Latin Vulgate into Middle English—the form of English used at the time. The Wycliffe Bible became widely circulated throughout England. Over 200 copies have survived to the present.

Officials of the Roman Catholic Church in England did not like this. It was a threat to their position and authority. Very quickly a council at Oxford issued a proclamation known as the Constitutions of 1408, forbidding translation of the Bible into English and possession of translations not approved by Catholic officials. Seven years later, the Council of Constance declared Wycliffe a heretic, banned his writings, and declared that his works and even bodily remains should be burned. Pope Martin V approved this ruling, and in 1428, Wycliffe’s body was dug up, burned, and his ashes were scattered on the River Swift. Despite efforts to suppress the reading and distribution of God’s word, it was too late—an interest in Scripture had been kindled in England that could not be snuffed out.

Over the next century, two developments changed the world forever: (1) the printing press, and (2) Christian Humanism. In 1452, a German blacksmith named Johannes Gutenberg successfully developed a printing press with movable type. At last, documents didn’t have to be written by hand! Type could be set and as many copies as the printer wanted could be made. At the same time, a resurgence of knowledge was going on in Europe. Since the fall of the Roman Empire learning had dwindled during the Dark Ages. The Renaissance ushered in a renewal of interest in the great advancements of classical Greek and Roman times that had been lost during the Middle Ages. In religious studies, this blossomed into a movement called “Christian Humanism.” A Dutch scholar named Desiderius Erasmus was at the heart of this. He studied Greek manuscripts of the New Testament looking beyond the Latin Vulgate translation that had dominated Western Europe for a thousand years. Like Wycliffe, he believed that the Bible should be accessible to all, but he looked back to the original text. In 1516, he began publication of critical editions of the Greek New Testament that were distributed throughout Europe. Although he remained a Catholic, his work, and that of scholars who followed him profoundly aided the Protestant Reformation and its call to follow “the Scriptures alone.”

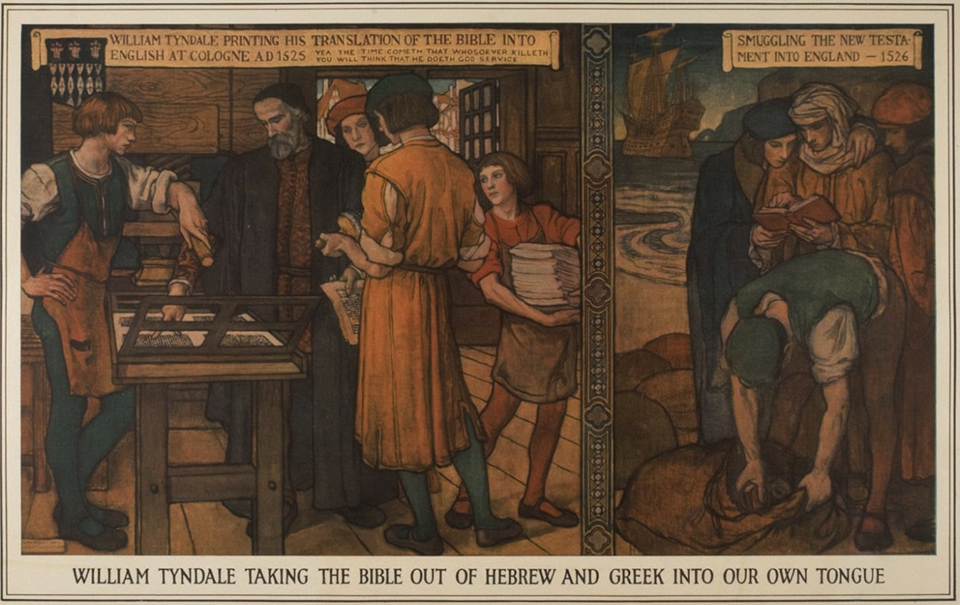

In 1522, using Erasmus’ Greek text, Martin Luther, the German monk who triggered the Reformation, produced the first translation of the New Testament into German. Erasmus had spent many years in England and even taught at Cambridge. Not long after he left, a brilliant student named William Tyndale came to the university. Tyndale mastered Greek and in 1523, sought permission from the Catholic bishop of London to produce an English translation of the New Testament. When his request was denied, he traveled to the European mainland, never to return to England. Tyndale quickly completed a translation of the New Testament from Greek into English. Evading Catholic enemies, he eventually succeeded in printing copies that were smuggled into England in bales of cloth and sacks of flour or corn. Catholic officials bought as many copies as they could, only to burn them, but many survived, and the English people, at last, had the New Testament in their language. In 1535, Tyndale was arrested and three years later was strangled to death and burned at the stake. His dying words were, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes!”

Mural by Violet Oakley from the Pennsylvania State Capital showing William Tyndale first printing the Bible in English and Bibles being smuggled into England.

The king of England was Henry VIII. Although he had been a Catholic, when the pope refused to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn, Henry rejected the authority of the pope, giving birth to the Church of England. The British Parliament had already rejected Roman authority when Tyndale was executed, but it had not yet approved the publication of English Bibles.

Following Tyndale’s death, two of his friends, Miles Coverdale and John Rogers, continued his work, publishing Bibles that included the Old Testament: the Coverdale Bible (1535) and Matthew’s Bible (1537). Unfortunately, they were not able to use the Hebrew text to translate the Old Testament. By 1539, the tide had shifted enough in England so that chancellor Thomas Cromwell, with the approval of the king, commissioned Miles Coverdale to revise the Matthew’s Bible, making use of Hebrew texts to translate the Old Testament. This work, known as the Great Bible was published in 1539, with a picture of Henry VIII on its cover page. 21,000 copies were circulated throughout churches in England.

While Henry VIII had broken ties with Rome, Catholic opposition was not yet finished. In 1546, a Catholic assembly, known as the Council of Trent, declared that the Latin Vulgate was the sole authoritative text in matters of faith and morals. Seven years later, Mary I, known to history as “bloody Mary,” came to the throne. A devout Catholic, Mary once again outlawed the reading of the Bible in English and executed her opponents. Many Puritans, who followed the teachings of John Calvin, fled to Geneva where they produced their own translation, incorporating Calvin’s commentary notes in the margins. The Geneva Bible (1557) was the most popular English Bible in the world until the publication of the King James Bible. It was the Bible the Pilgrims brought to North America. After the death of Mary I, her half-sister, Elizabeth I, reversed what Mary had done. She objected to the Calvinistic notes in the popular Geneva Bible, and sponsored a revision of the Great Bible done by eight bishops called the Bishop’s Bible (1568), placing one in every church in England.

Near the close of the sixteenth century, the Catholic church finally conceded that an English Bible was inevitable. In 1582, using the Latin Vulgate as its basis, the Rheims-Douay Bible was produced and became the official Catholic Bible until the twentieth century. Finally, when James I took the throne, he reached an agreement with the Puritans and assigned forty-seven scholars to make a translation (without commentary notes) to stand as an “Authorized Version.” Working in six groups for seven years, in 1611 the King James Bible was produced. It became not only the most popular English Bible but the most influential English book in human history. In 1873, it was revised by the Church of England and continues to be used by many today.